The quiet disappearance of giraffes is taking Rockwood on a journey of discovery

Africa’s giraffe populations are quietly diminishing. Known as the “silent extinction”, 40% of giraffes have vanished since the 1980s. Where once the continent was teeming with these graceful giants, only 68 000 now remain. Like most other African species, habitat loss, poaching and the effects of civil unrest threaten the survival of giraffes.

Considered “easy prey”, they are especially targeted by poachers for the bushmeat trade. Trading in giraffe ‘products’ is also rife. In some countries, giraffe bone marrow and brains are considered a cure for HIV/AIDS.

Of the species with nine sub-species, six are listed on one of the threatened categories, ranging from near threatened to critically endangered. Two are not yet assessed and one is least concerned. In 2019, giraffes were protected with an Appendix II listing by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). While this doesn’t ban all international trade of the species, it does impose stringent conditions to restrict buying and selling giraffe parts.

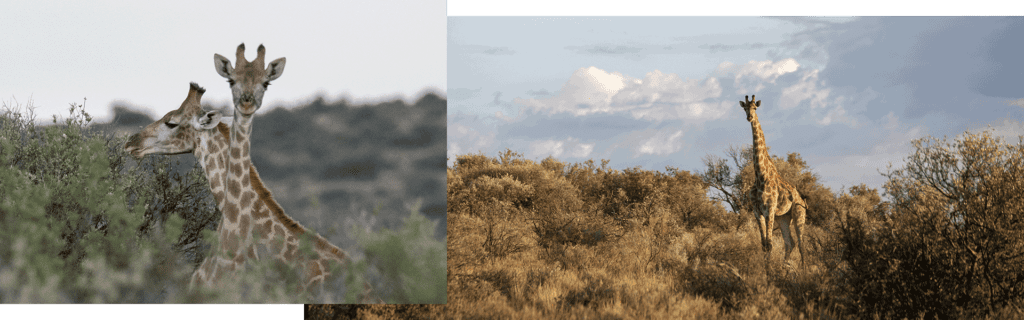

Fortunately, giraffe numbers are increasing in Southern Africa due to conservation efforts, including the number of private reserves that protect them.

At Rockwood, we protect a small population of giraffes on our reserve. As well as safeguarding our small “journey”, we also use the group to conduct valuable conservation research. Historically overlooked in terms of research and conservation, we are part of a new conservation movement to save giraffes against extinction.

ROCKWOOD GIRAFFE RESEARCH

Our giraffe research involves the non-invasive collection of hormonal data. We use the data to ascertain stress levels in giraffes to improve the process of relocating the animals. Relocating giraffes to create viable breeding herds, or to reintroduce giraffes to new areas, forms a major part of conserving and managing their populations. The data helps us improve relocation methods in lowering the animal’s stress levels during the process.

To do this, we test for faecal glucocorticoid metabolites which helps us see the level of stress hormones in the animal’s bodies. Glucocorticoids is a steroid stress hormone. A better-known steroid stress hormone is cortisol, but glucocorticoid works similarly.

To test metabolites of the hormone levels, we followed the giraffes on horseback until we see them defecating. Then we quickly collect the faeces for testing. The samples must be less than half an hour old when collected as the metabolism of the hormone continues even outside the body.

In other words, we do not measure their exact hormone levels, but instead the metabolites of the hormones. So, the higher the metabolite levels, the higher the hormones in the body. To measure exact levels, you would have to draw blood which in turn is invasive and stressful for the animal. As a result, you wouldn’t see the effect of the translocation on their stress levels, as you would instead be measuring their stress of capturing and drawing blood.

Adding to the hormone research, our conservation scientist, Ciska Scheijen, has also co-written and published papers on the viability and considerations of giraffe translocations.

At Rockwood, we’re doing whatever we can to safeguard vulnerable species for future generations. But we can’t do it alone. We need your help.